Pregnant women experience numerous adjustments in their endocrine system that help support the developing fetus. The fetal-placental unit secretes steroid hormones and proteins that alter the function of various maternal endocrine glands. Sometimes, the changes in certain hormone levels and their effects on their target organs can lead to gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension.

Fetal-placental unit

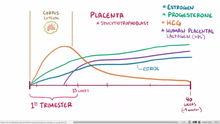

Graph of the levels of estrogen, progesterone, beta-hcg throughout pregnancy

Levels of progesterone and estrogen rise continually throughout pregnancy, suppressing the hypothalamic axis and subsequently the menstrual cycle. The progesterone is first produced by the corpus luteum and then by the placenta in the second trimester. Women also experience increased human chroinic gonadotropin (β-hCG), which is produced by the placenta.

Pancreatic Insulin

The placenta also produces human placental lactogen (hPL), which stimulates maternal lipolysis and fatty acid metabolism. As a result, this conserves blood glucose for use by the fetus. It can also decrease maternal tissue sensitivity to insulin, resulting in gestational diabetes.

Pituitary gland

The pituitary glands grows by about one-third as a result of hyperplasia of the lactrotrophs in response to the high plasma estrogen. Prolactin, which is produced by the lactrotrophs increases progressively throughout pregnancy. Prolactin mediates a change in the structure of the breast mammary glands from ductal to lobular-alveolar and stimulates milk production.

Parathyroid

Fetal skeletal formation and then later lactation challenges the maternal body to maintain their calcium levels. The fetal skeleton requires approximately 30 grams of calcium by the end of pregnancy. The mother’s body adapts by increasing parathyroid hormone, leading to an increase in calcium uptake within the gut as well as increased calcium reabsorption by the kidneys. Maternal total serum calcium decreases due to maternal hypoalbuminemia, but the ionized calcium levels are maintained.

Adrenal goals

Total cortisol increases to three times of non-pregnant levels by the third trimester. The increased estrogen in pregnancy leads to increase corticosteroid-binding globulin production and in response the adernal glad produces more cortisol. The net effect is an increase of free cortisol. This contributes to insulin resistance of pregnancy and possibly striae.Despite the increase in cortisol, the pregnant mom does not exhibit Cushing syndrome or symptoms of high cortisol. One theory is that high progesterone levels act as an antagonist to the cortisol.

The adrenal gland also produces more aldosterone, leading to an eight-fold increase in aldosterone. Women do not show signs of hyperaldosterone, such as hypokalemia, hypernatremia, or high blood pressure.

The adrenal gland also produces more androgens, such as testosterone, but this is buffered by estrogen’s increase in sex-hormone binding globulin (SHBG). SHBG binds avidly to testosterone and to a lesser degree DHEA.

Thyroid

The thyroid enlarges and may be more easily felt during the first trimester. The increase in kidney clearance during pregnancy causes more iodide to be excreted and causes relative iodine deficiency and as a result an increase in thyroid size. Estrogen-stimulated increase in thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) leads to an increase in total thyroxine (T4), but free thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) remain normal.